(Using another tool? Please select it now: Pyret.)

Students create and interpret dot plots, considering the distribution and typicality of the data. Students define variability multiple ways, and then describe different levels of variability that they observe on dot plots.

Lesson Goals |

Students will be able to…

|

Student-facing Lesson Goals |

|

Materials |

|

🔗Dot Plots' Distribution and Typicality

Overview

Students create and interpret dot plots, learning new vocabulary to informally describe a dataset’s distribution and typicality.

Launch

Draw or project a number line on a piece of chart paper or on the board. Your number line should start at zero and go up to 15 by ones. If you have a student with a name that is more than 15 letters, extend the number line accordingly.

-

Count how many letters are in your first name.

-

Once you have counted, line up at the board to draw a dot above the number of letters in your first name.

-

You may stack dots, but try to keep them evenly spaced.

-

Take a look at the results of our survey displayed on the Board.

-

What do you Notice?

-

What do you Wonder?

Now that your individual name length is represented in our class dot plot…

-

Turn to Our Class' Name Length Data and copy each of the dots from the class dot plot onto the number line in the top section.

-

Put Our Class' Name Length Data aside for now. We will return to it later in the lesson.

Dot Plots?!

If you teach students who are older than 10 or 11 years old, you may be asking yourself: Why dot plots? Aren’t those a little elementary?

Students are generally successful interpreting dot plots (compared to, say, box plots and histograms) because on a dot plot, individual cases are visible. Educational research tells us that interpreting box plots and histograms is often difficult for students because they tend to view data as individual cases. Box plots and histograms only provide an aggregate view.

To combat this challenge, Bakker, Biehler, and Konold (2005)Bakker, A., Biehler, R., & Konold, C. (2005). Should young students learn about box plots? In G. Burrill & M. Camden (Eds.), Curricular Development in Statistics Education: International Association for Statistical Education (IASE) Roundtable, Lund, Sweden, 28 June-3 July 2004. recommend building a strong foundation with data visualizations where individual cases are visible. In short: don’t gloss over dot plots! When introducing box plots and histograms, the research recommends pairing the less-familiar aggregate data visualizations with their corresponding (familiar) dot plots as we do in this lesson and others.

Investigate

-

Turn to Interpreting Dot Plots and complete the first section: Reading a Dot Plot.

-

Be prepared to discuss your answers with the class.

Review students' responses as a class. Questions 1, 2, and 3 touch on three relevant concepts: range, mode, and proportional reasoning.

Now that we are comfortable reading dot plots, we need a common vocabulary to discuss the data that they display. To describe the distribution of data—the way that it is spread out on a number line—it is helpful to locate any outliers, clusters, peaks, and gaps.

-

A cluster is a group of data points that are close together.

-

A gap is an interval where there are no data points.

-

An outlier occurs when one data point is much larger or smaller than the other data points.

-

A peak is the value(s) with the most data.

-

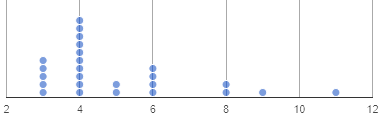

Let’s complete the second section of Interpreting Dot Plots together using the data in the dot plot for Group A.

-

What peaks should we label?

-

There is a peak at 4.

-

What clusters should we label?

-

There is a cluster from 3 to 6.

-

What gaps should we label?

-

There are gaps at 7 and 10.

-

What outliers should we label?

-

There is an outlier at 12.

-

Now let’s turn to question 5. What do those peaks, clusters, gaps, and outliers tell us about the dataset?

Complete the third section of Interpreting Dot Plots with your partner.

Discuss and review students' responses. Students will complete the final section of Interpreting Dot Plots after a brief class discussion on typicality.

Another way of describing data on a dot plot is to think about its typicality.

-

Let’s think about the word "typical". Describe a "typical" morning for you.

-

Invite students' to share. Emphasize that "typical" is "the usual", or "what’s expected", but it is not always a perfect predictor. It may be "typical" to eat breakfast at 7am, but there are probably days where you eat a little bit earlier or a little bit later — or even much earlier or much later!

-

What does the word "typical" mean to you?

Complete the final section of Interpreting Dot Plots.

Review students' responses, emphasizing that there are multiple ways to decide what is typical in a dataset. You may want to highlight a few different and appropriate responses to highlight that we are simply estimating typicality. Some students may have located the most common value (or mode), while others may have found the middle value (median), or the balance point of the data (mean).

Let’s read and interpret the dot plot representing our class' name length data.

-

With a partner, complete Our Class' Name Length Data.

-

In what ways was our class data similar to the data from Group A and/or Group B on Interpreting Dot Plots?

-

Was there anything that made our class data unique?

Synthesize

-

When determining what value is typical, why was it helpful to consider peaks, clusters, gaps, and outliers in the dataset?

-

A peak indicates a name length that is the most common—which is one way of thinking about what’s typical.

-

There might be a cluster where most of the data falls, which would likely be where would locate what’s typical.

-

If we want to find a balance point for all of the data (yet another way of thinking about what is typical), then we need to consider gaps and outliers.

-

What were some of the different strategies you used to choose a typical value in the dataset?

-

This question is designed to prime students to recognize that what’s typical generally exists at the center of the data. Students will likely identify the values that (approximately) represent the mean, median, and mode(s). It is fine if students are not yet able to recognize these measures of center, which they will explore during Measures of Center.

🔗Variability Two Ways

Overview

Students define variability two ways, and then apply that understanding to describe the variability of categorical and quantitative data.

Launch

In our discussion of dot-plots, we learned to describe the distribution of a dataset in terms of outliers, clusters, peaks, and gaps. We also considered what’s typical — or expected — in the data. This lesson focuses on another way to describe a dataset: its variability.

Statistical questions are questions that anticipate variability.

-

Which question anticipates variability:

How many minutes are in an hour?

How many minutes does it take to get to school?

Explain your response. -

Question B anticipates variability. The time it takes to drive to school will vary based on who you ask, where they live, mode of transportation, time of day, road conditions, traffic, etc.

-

The answer to Question A will always be 60.

Statistical questions tend to be interesting questions! To answer them, we must do some sort of research or data collection. Statistical questions are often best asked with "in general" attached, because the answer isn’t black and white.

There are Many Ways to Think about Variability!

Research indicates that students often have an oversimplified and underdeveloped view of variability (Cooper, 2018Cooper, L. (2018). Assessing Students’ Understanding of Variability in Graphical Representations that Share the Common Attribute of Bars. Journal of Statistics Education, 26(2), 110–124.; Cooper & Shore, 2008Cooper, L., & Shore, F. S. (2008). Students’ Misconceptions in Interpreting Center and Variability of Data Represented via Histograms and Stem-and-Leaf Plots. _Journal of Statistics Education, 16(2), 1.).

In this lesson, we intentionally begin our conversation by developing intuitive ideas about variability, for instance:

-

Variability requires us to consider the data as an entity, rather than as individual points.

-

We can try to understand why things vary and try to identify reasons for variability.

-

Some things vary a little, and some vary a lot.

-

We see variability in both quantitative and categorical datasets.

This last recommendation is an important one: research indicates that it is more natural to understand how like or unlike categorical data is than it is to understand variation about the mean (Kader & Perry, 2007G.D. Kader, M. Perry, Variability for categorical variables, Journal of Statistics Education, 15(2) (2007).), therefore reasoning about variability in categorical datasets can act as a natural starting point.

That said, we urge you to explicitly emphasize that how alike or different the data points are is just one of many ways to think about variability. Fixating on this definition of variability can result in students developing the common misconception that levelness of histogram bars indicates low variability (Cooper & Shore, 2008Cooper, L., & Shore, F. S. (2008). Students’ Misconceptions in Interpreting Center and Variability of Data Represented via Histograms and Stem-and-Leaf Plots. _Journal of Statistics Education, 16(2), 1.).

Investigate

In a categorical dataset, we can judge variability based on how different or alike the data points are. Let’s think about the variability of some categorical datasets.

-

Complete the first section of questions on Two Ways of Thinking about Variability.

-

Then we’ll pause to discuss them as a class.

-

In Sana’s grocery bag, she has 12 apples and 1 banana. In Juliette’s grocery bag, she has 4 peaches, 4 kiwis, 4 oranges, and 1 limes. Which dataset — Sana’s groceries or Juliette’s groceries — has greater variability?

-

Sample response: Juliette’s grocery bag has greater variability, as the items in her bag are more different from one another than the items in Sana’s bag. If students are inclined to consider the amount of each item, remind them that this is a categorical dataset.

-

You ask a group of sixth grade students to respond to two different statements with either "true" or "false." Statement A is I am in sixth grade, and statement B is I am wearing blue today. Which statement do you predict will produce greater variability?

-

Sample response: Given that the students you are sampling are in sixth grade, there will not be any variability in their responses to statement A. Everyone will choose "true". For statement B, however, we expect variability, because it is likely that some students will be wearing blue and some will not".

Complete Two Ways of Thinking about Variability.

-

Do you agree or disagree that students in our class generally have the same number of letters in our first name?

-

Sample response: I disagree. The data spreads out from 3 letters to 14 letters. If all students had the generally same number of letters in their names, most or all of name lengths would be equivalent.

-

Which dataset do you predict will have greater variability for a group of ninth graders who attend the same school — Wake-up times on Wednesday or Saturday?

-

Sample response: Saturday wake-up times probably has greater variability. On a school day, everyone needs to wake up in time to get to school, but on Saturday, some students may choose to sleep in later.

Students often believe that variability can be judged based solely on the range of a dataset (Cooper & Shore, 2008Cooper, L., & Shore, F. S. (2008). Students’ Misconceptions in Interpreting Center and Variability of Data Represented via Histograms and Stem-and-Leaf Plots. _Journal of Statistics Education, 16(2), 1.). Although we will focus on range for the remainder of this lesson, acknowledge to students that there are many other ways to quantify variability. The dialogue about variability that begins in this lesson will continue (and gain nuance) during our lessons on Histograms: Visualizing "Shape", Introduction to Box Plots, and Standard Deviation.

Synthesize

Before facilitating a whole class discussion, you might want to have students exchange the datasets they made on the third section of Two Ways of Thinking about Variability with a partner and discuss their strategies for determining the variability of each dataset.

-

How did your strategies for assessing variability change, if at all, when you looked at a categorical dataset versus a quantitative dataset?

-

If two datasets have the same range, how can we decide which one has greater variability?

-

Although students will probably not be able to answer this question concretely (e.g. use interquartile range, mean absolute deviation, or standard deviation), it is a good opportunity to see if they are developing intuition about variability as deviation from the center. You can invite students to share, and then reveal that they will uncover the answers to this question later!

🔗Visualizing Variability with Dot Plots

Overview

Students connect dot plots to different scenarios based on the variability. They learn how to create dot plots in CODAP to investigate the distribution of data in dot plots.

Launch

Let’s investigate how different levels of variability appear on dot plots.

-

The person who created the dot plots on Variability of Dot Plots forgot to label them.

-

To complete the page: Fill in the blanks in the first column with either "A" (if the description matches dot plot A) or "B" (if the description matches dot plot B), then explain your choice in the last column.

-

What strategies did you use to match labels with dot plots?

-

Possible responses: I considered the range of the data; I asked myself which scenario would produce data with greater variability; I envisioned in my head what the dot plot would look like, etc.

-

Can you think of any similar pairs of datasets that would produce dot plots with differing levels of variability?

-

Possible responses: minutes 9 year-olds spend talking on the phone versus minutes 18 year-olds spend talking on the phone; time to run a mile for professional athletes versus a group of high school students; etc.

Investigate

The folks at the animal shelter want to approximate the amount of food they need to purchase for the coming month. They know there is a relationship between an animal’s weight and how much it eats, so they are discussing the distribution of animals' weights.

-

With a partner, complete the first section of Variability of Animals' Weights.

Review students' responses, first ensuring that students are able to estimate what’s typical in a dataset (question 1).

-

How did you decide what species has the greatest and least variability?

-

Responses will vary. Ideally, students are thinking about the possible weight range for each animal, recognizing that there are some extremely large breeds of dogs, but that most tarantulas are generally the same size.

-

How did you describe the distribution of dogs' weights?

-

Responses will vary. Students should acknowledge that a peak exists at approximately 55 pounds, and that there is a gap between the cluster of light- to mid-weight dogs and the few very heavy outliers.

It’s time to make dot plots in CODAP!

-

Open the Dogs, Rabbits, Cats & Tarantulas Starter File and click "Run".

-

Use it to complete the second section of Variability of Animals' Weights, making dot plots for each species in CODAP and responding to the prompts on the table.

We’ve defined some helper functions in rows 15-18 of the Dogs, Rabbits, Cats & Tarantulas Starter File. Interested students can learn more about helper functions during Filtering and Building. Students need not develop a strong understanding of helper functions to complete the activities in this lesson.

Synthesize

-

You’ve been asked to estimate what’s typical of a dataset several times. How do you think the variability of a dataset affects typicality?

-

When a dataset is highly variable, the spread is wide and there is a greater likelihood that there are outliers; both of these affect typicality. For instance, a high outlier on the right increases what’s typical. If there is low variability, it is generally easier to predict what is typical. If there is no variability, we know what is typical because the dataset contains only a single value.

These materials were developed partly through support of the National Science Foundation, (awards 1042210, 1535276, 1648684, 1738598, 2031479, and 1501927).  Bootstrap by the Bootstrap Community is licensed under a Creative Commons 4.0 Unported License. This license does not grant permission to run training or professional development. Offering training or professional development with materials substantially derived from Bootstrap must be approved in writing by a Bootstrap Director. Permissions beyond the scope of this license, such as to run training, may be available by contacting contact@BootstrapWorld.org.

Bootstrap by the Bootstrap Community is licensed under a Creative Commons 4.0 Unported License. This license does not grant permission to run training or professional development. Offering training or professional development with materials substantially derived from Bootstrap must be approved in writing by a Bootstrap Director. Permissions beyond the scope of this license, such as to run training, may be available by contacting contact@BootstrapWorld.org.