Having deciphered the patterns in a dataset with perfect periodic (sinusoidal) behavior, students build and work with a model for data about Carbon Dioxide that has more variability.

Lesson Goals |

Students will be able to…

|

Student-facing Lesson Goals |

|

Materials |

|

🔗Fitting Periodic Models

Overview

Students explore the CO2 dataset, which tracks the recorded quantity of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere from the Mauna Loa observatory in Hawaii beginning in 1974.

Launch

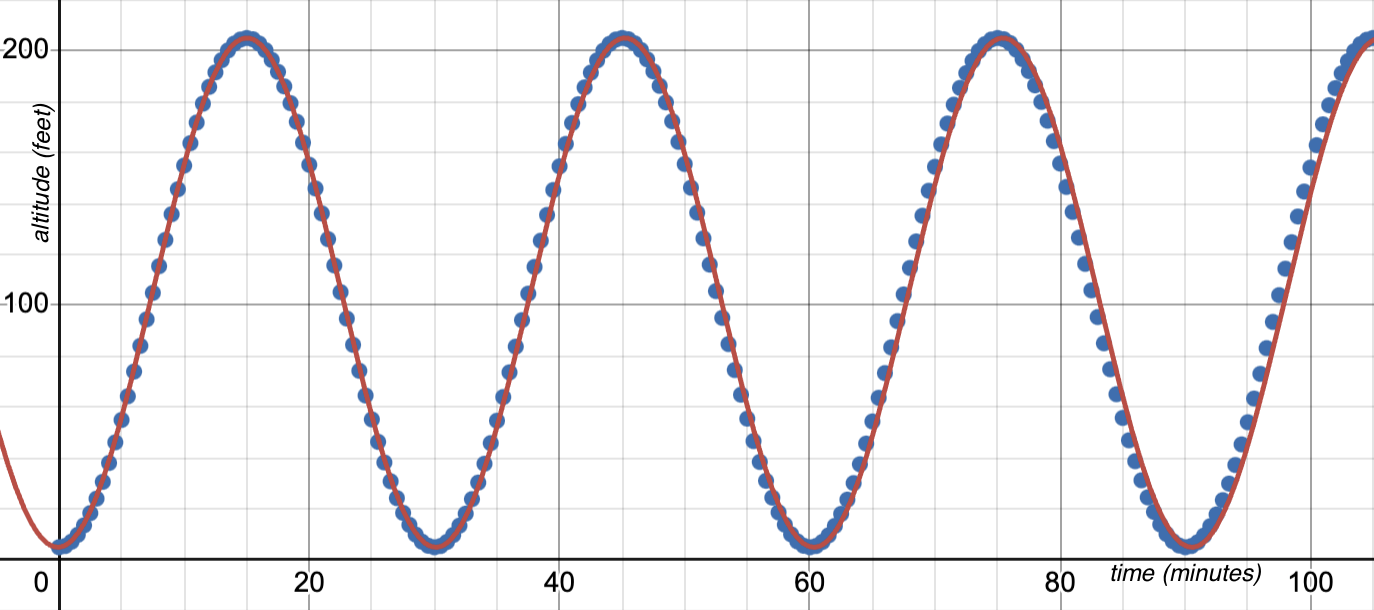

The Ferris wheel dataset lined up perfectly with a periodic model because it had almost no variability:

the wheel didn’t change size or speed and there aren’t any other variables influencing the data.

The Ferris wheel dataset lined up perfectly with a periodic model because it had almost no variability:

the wheel didn’t change size or speed and there aren’t any other variables influencing the data.

The real world is never this simple! Now that we’ve started to understand how periodic models work, it’s time to add them to our toolkit and look at a more realistic — and messy! — dataset.

Carbon Dioxide (CO2) is:

-

the gas inside the bubbles in a can of soda

-

what we breathe out when we exhale

-

dry ice (in solid form)

-

known as a "greenhouse gas", because, when enough of it is in the atmosphere, it traps heat and contributes to global warming

Because scientists are concerned about how much carbon dioxide is in the atmosphere, they take frequent measurements from multiple locations around the globe in parts-per-million (abbreviated as ppm). There are many things that can influence the amount of CO2 in any one location over the course of time. Some of these factors include:

-

temperature and air pressure

-

proximity to carbon-dioxide-producing sources or carbon-dioxide-consuming features

-

global trends like the burning of fossil fuels

But is there a pattern?

-

Open the Carbon Dioxide Starter File.

-

Save a copy that’s just for you, and click "Run".

-

What is the name of the table here?

-

co2-table

-

What are the names of the columns?

-

year, month, data, co2

-

Type

co2-tableinto the Interactions Area, and look at the table.

What do theyear,month, andco2columns mean? -

yearis pretty self-explanatory, e.g. 1974 in the first row indicates that the first measurement was recorded in the year 1974. -

monthis a number from 1 to 12. The 5 in the first row corresponds to May. -

co2is the carbon dioxide level in parts per million as measured at the Mauna Loa Observatory in Hawaii. In May of 1974 they recorded 333.18 ppm of CO2. -

The numbers in the

datecolumn look pretty different from dates we are used to seeing. What do you think they tell us? -

(Students answers will vary — see explanation below)

The date column provides us with something known as the decimal year. When reading a decimal year, we see the year followed by the decimal that results when the nth day of the year is divided by 365.

For inquiring students, you may need to know that during a leap year, the decimal year is calculated by dividing by 366. (1974 was not a leap year. The next leap year was 1976.)

The first date is 1974.375, meaning the sample was taken 0.375 of the way through 1974.

-

How could we compute which day of the year that is?

-

There are 365 days in the year, so we could multiply 365 by

0.375to see the number of days into the calendar. -

365 × 0.375 = 136.875, or roughly day 137

-

Does that day correspond to the "month-number" in the

monthcolumn for the first row? -

Yes. The "month-number" is 5 for May. And the 137th day of a non-leap year is May 17th.

-

Now that we know what each of the columns mean, take another look at the dataset.

-

What do you Notice?

-

What do you Wonder?

Let’s turn our attention back to the Definitions Area. Find the function is-recent.

-

What does

is-recentdo? -

It takes in a row, and checks to see if the decimal date is between 2022.083 and 2023.7917.

-

What is defined on the line of code that follows?

-

A table, which contains only the rows for which the filter function produces

true. In other words, a table that contains just the rows between those dates.

The recent-table includes just the rows from valley-to-valley for the years 2022-2023. It defines a single period.

Investigate

-

Complete Modeling Recent Carbon Dioxide Levels using the Carbon Dioxide Starter File.

-

Be ready to share your answers!

-

What was the highest CO2 value in the table? The lowest?

-

424 and 415.74 parts per million.

-

What did you get for amplitude a?

-

4.13, because the distance between the high and low readings is 8.26.

-

What did you get for the vertical shift k?

-

Adding the amplitude (4.13) to the lowest value (415.74) gives us 419.87.

-

What did you estimate for the phase shift d?

-

Answers will vary, but should be close to 2023.1

-

How many years make up one period?

-

One year (this makes sense, since the seasonal cycle repeats every year!)

-

What did you get for frequency b?

-

2π, because the period is 1 year and $$\displaystyle {2\pi \over\displaystyle 1} = 2\pi$$.

As we know, frequency can be calculated from the period and vice-versa. While the model is built using the frequency, the period will be a much more intuitive measure for students in making sense of what we expect the data to do.

We can make a periodic model using sine or cosine (each one is a horizontal shift away from the other, so they are interchangeable!). For now, let’s work with periodic models that use sin.

-

Let’s use these values to construct our

periodic-sinmodel, and then fit our model to the data in Pyret! -

With your partner, complete Modeling Recent Carbon Dioxide Levels (continued).

-

When you look at the

periodic-sinmodel graphed on therecent-tablescatter plot, do you think it makes sense to use a periodic model for this data? Why or why not? -

Yes. The data points move up and down along either side of the curve.

-

How does this model for the CO2 data compare to the model we saw for the ferris wheel data?

-

All of the points for the ferris wheel data fell on the curve.

-

Our CO2 data falls near the curve, but not on it.

-

Samuel says that the

periodic-sinmodel is a good fit for the data in therecent-table.

Would you strongly agree, agree, disagree, or strongly disagree with that statement? Justify your decision based both on what you see in the model and using the S-value. -

Agree. While none of the points are on the curve, they don’t stray very far from it.

-

Also, the data in the

recent-tableranges from 415.91 to 424 and the S−value tells us to expect an error of about 1.2 ppm of CO2 in predictions made with the model. -

Linear regression allows us to find the computationally optimal model, not just a model that "fit really well." Do we know whether or not our model is the best?

-

We don’t know!

Synthesize

We just built a model from a sample for predicting CO2 levels.

-

Why might data scientists build a model from a sample?

-

In the real world it is pretty rare to have access to every piece of data we can imagine wanting to work with, so sometimes all we have is a sample.

-

What limitations are there to building a model from a sample?

-

The predictions a model will make will be most accurate for the range of data it is built on. Data beyond that range might exhibit other trends.

-

The pattern we find in a sample could be unrepresentative of the patterns in the whole.

Optional Activity: Guess the Model!

-

Divide students into small groups (2-4), and have each team come up with a periodic, real-world scenario, then have them write down a periodic function that fits this scenario on a sticky note. Make sure no one else can see the function!

-

On the board or some flip-chart paper, have each team draw a scatter plot for which their periodic function is best fit. They should only draw the point cloud — not the function itself! Finally, students title their scatter plot to describe their real-world scenario (e.g. "Water depth at a beach vs. Time of Day").

-

Have teams rotate so that each team is in front of another team’s scatter plot. Have them figure out the original function, write their best guess on a sticky note, and stick it next to the plot.

-

Have teams return to their original scatter plot, and look at the model their colleagues guessed. How close were they? What strategies did the class use to figure out the model?

-

The model settings can be constrained to make the activity easier or harder. For example, limiting these model settings to whole numbers, positive numbers, etc.

-

To extend the activity, have the teams continue rotating so that each group adds their sticky note for the best-guess model. Then do a gallery walk so that students can reflect: were the models all pretty close? All over the place? Were the guesses for one model setting grouped more tightly than the guesses for another?

-

These materials were developed partly through support of the National Science Foundation, (awards 1042210, 1535276, 1648684, 1738598, 2031479, and 1501927).  Bootstrap by the Bootstrap Community is licensed under a Creative Commons 4.0 Unported License. This license does not grant permission to run training or professional development. Offering training or professional development with materials substantially derived from Bootstrap must be approved in writing by a Bootstrap Director. Permissions beyond the scope of this license, such as to run training, may be available by contacting contact@BootstrapWorld.org.

Bootstrap by the Bootstrap Community is licensed under a Creative Commons 4.0 Unported License. This license does not grant permission to run training or professional development. Offering training or professional development with materials substantially derived from Bootstrap must be approved in writing by a Bootstrap Director. Permissions beyond the scope of this license, such as to run training, may be available by contacting contact@BootstrapWorld.org.